The first Hot Thing IN Tox is a study looking at drugs of abuse in the community. Dear Friends working at Methodist– please call the poison center (317-962-2323) for those individuals who you suspect are intoxicated with an illicit substance. It doesn’t matter if the patient is admitted or discharged. If you don’t have time to call, send me an email with the patient’s MRN (include phrase “secure message” in the subject line). The end goal of the study is to identify what crazy things people are taking these days- via a novel detection method. Of course, if you wouldn’t mind hearing a bit of advice as to how to manage the patient, we are happy to help, as always.

What else is Hot in Tox? Drugs in the water. Some of you may have seen this recent article:

https://www.npr.org/2019/05/02/719600999/traces-of-cocaine-pesticides-detected-in-u-k-shrimp

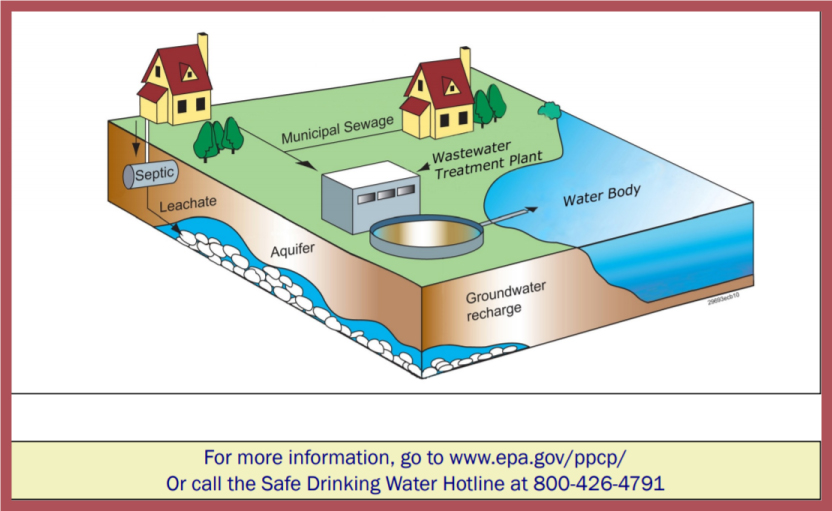

Using sewage to help determine patterns of drug use is not a new technique. Europe has been doing studies of this kind for a long time, and America has a few researchers using this method as well. The theory is that people consume illicit substances, and then their urine and feces contain the evidence which can be analyzed at the point it enters sewers or water treatment plants. Drugs often make it through the treatment plants without being removed or broken down, and then the effluent enters water supplies and the food chain. Filter feeders, such as shellfish are used by researchers to test for environmental contaminants, as they are generally the first type of organism to collect and concentrate substances released in water. Perhaps, like me, you find it disturbing that drug metabolites are being found in something that you could potentially consume in your diet, especially if those metabolites were previously excreted by a person abusing illicit substances.

https://gizmodo.com/sewage-study-finds-american-drug-use-may-be-worse-than-1828472296

If that is disturbing though, it is even more horrifying to think of all the potential drug and medication exposures in the water supply. Physicians routinely prescribe medication to treat various ailments, but patients have not been shown to be perfectly compliant with taking all the medication we prescribe. In fact, ‘perfect’ is a far cry from the actual behavior of the majority of our patients. Many people will quit taking their medication while some remains in the prescription- some because they don’t perceive a need, some because the need has passed, some just aren’t all that into taking pills in the first place.

It is estimated that between 45-75% of people who were prescribed opiates will not finish the entire prescription.1 People find it tempting to share their prescription opioids with friends and family who have painful conditions. Most individuals who have leftover narcotics will keep the unused portion for potential need in the future, and very few will make the effort to bring the drugs to a take-back site. Having unused narcotics in the home increases the chance of an accidental exposure (pediatric exploratory, or mistaken identity of pill bottles by another individual) and likely also increases diversion.1 In a study conducted from 2007-2011, children less than 6 years old were identified as having sought medical care because of accidental exposure to medication. Over this time, 35,000 emergency department visits occurred, and approximately 9500 hospitalizations occurred per year. Opioids and benzos were the most common classes involved in the hospitalizations (28%), but the most common single drugs were buprenorphine and clonidine (combined, caused about 15%).2

Given that having excess unneeded drugs floating around the home is a clear and present danger, would it not be better to get rid of them? It would seem an easy answer is yes- yes it would be much much better! Way better! But then when one contemplates what that means, the benefits become somewhat cloudier. How is one to dispose of medication?

Medications that are no longer needed could be flushed down your toilet, but doing this could result in those medications entering our drinking water supply. Water treatment plans are not equipped to remove medications from the water before it reenters rivers/lakes streams.3 Those put in landfills can also leech into ground water.

Oxycodone was detected in mussels in Washington state, along with a wide range of other medications.5 Fish are also shown to have trace amounts of drugs – all of which has a yet to be determined impact on the environment.

Some of the medications come from individuals throwing medications away, but a medical facilities are likely the largest contributors. Medications are wasted from hospitals/ECFs/clinics constantly- either the medication expires, a partial vial is used, or a change in medication occurs after a patient fills their prescription. One investigation estimated that 250 million pounds of pharmaceuticals and contaminated packaging is disposed of by medical facilities.

So it would appear that indiscriminate flushing/pitching/discarding of medications is not particularly good for any living thing. But what is a body to do? The EPA suggests that the order of preference for disposing of unwanted medication is:8

- Medication take back program

- Dispose of in the trash (after careful packaging in a container with unpalatable substance)

- Flush certain high risk medications down the toilet or drain

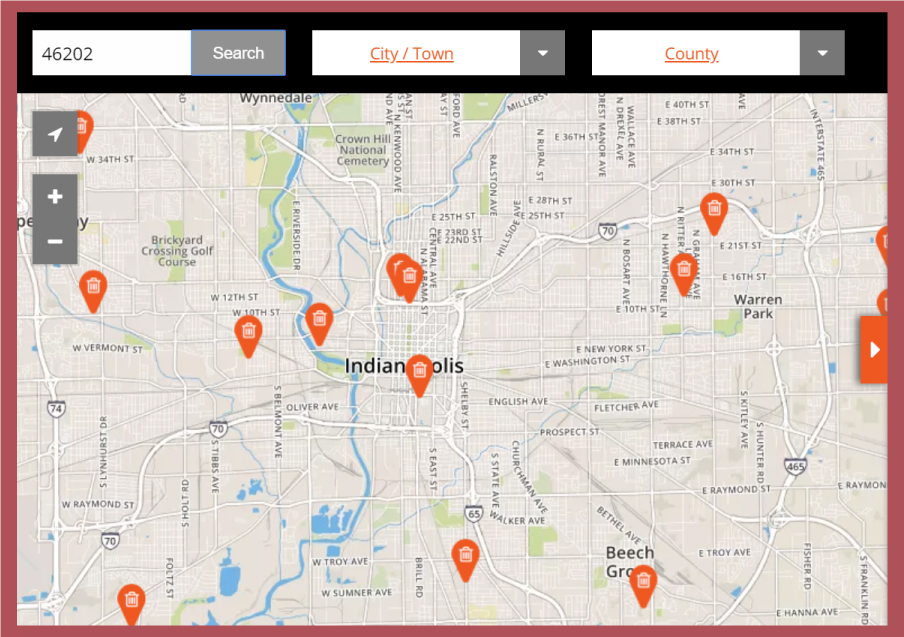

Where can one take one’s meds that one no longer needs? Excellent question! I’m thrilled you asked. Check out this website: https://www.in.gov/idem/recycle/2343.htm

Here you will find a lovely map of various sites that accepts leftover meds.

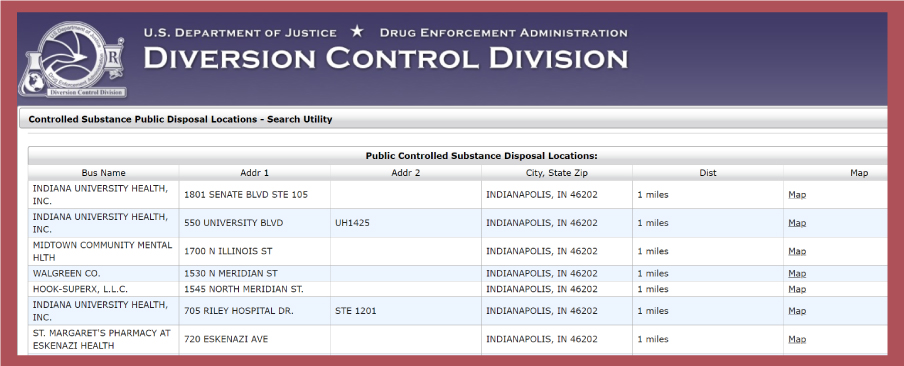

If one wants specifically to get rid of narcotics, the DEA also provides a list of places with take-back programs, although in a less attractive format.

https://apps.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/pubdispsearch/spring/main?execution=e1s1

If one were to be unable to find a close take-back site or be unwilling or unable to travel there, the FDA considers some medications just plain too dangerous to keep around. They provide a list of medication formulations that are deemed too risky to keep in a home with no intended immediate purpose. The list is composed almost completely of high potency opioids, with only a few exceptions. These include rectal diazepam gel, methylphenidate transdermal patches, and sodium oxybate (essentially is GHB). The rational is stated as: There is a small number of medicines that may be especially harmful and, in some cases, fatal with just one dose if they are used by someone other than the person for whom the medicine was prescribed. This list from FDA tells you what expired, unwanted, or unused medicines you should flush down the sink or toilet to help prevent danger to people and pets in the home.8

Oliver Wendell Holmes is widely quoted as saying, “If all the medicine in the world were thrown into the sea, it would be bad for the fish and good for humanity.” However, modern science would argue that not only are medications potentially not just a little bad for all of our animal friends (fish included), but perhaps very bad for them and therefore us also as consumers and technically organisms dependent on a stable ecosystem.

Acknowledgements: Marshall Haynick, our pharmacy fellow, gathered most of the information used in this story.

- Khan U, Bloom RA, Nicell JA, Laurenson JP. Risks associated with the environmental release of pharmaceuticals on the U.S. Food and Drug Administration “flush list”. Sci Total Environ 2017;609:1023-40.

- Lovegrove MC, Mathew J, Hampp C, Governale L, Wysowski DK, Budnitz DS. Emergency hospitalizations for unsupervised prescription medication ingestions by young children. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1009-e16.

- How to Dispose of Medicines Properly. In: Agency USEP, ed.2009.

- Aw, shucks: Oysters found to have traces of different medicines. STAT, 2016. (Accessed Feb 17, 2019, at https://www.statnews.com/pharmalot/2016/05/06/oysters-traces-of-medicines-drugs/.)

- Roma V. Traces of opioids found in seattle area mussels. The Two Way: NPR; 2018.

- Gabriel Eckstein,Drugs on Tap: Managing Pharmaceuticals in Our Nation’s Waters, 23N.Y.U. Envtl. L.J.37 (2015). Available at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/facscholar/690.

- Gorman J. A Drug Used for Cattle Is Said to Be Killing Vultures. The New York Times 2004:3-.

- Food U, Administration D. Disposal of unused medicines: what you should know. 2016.